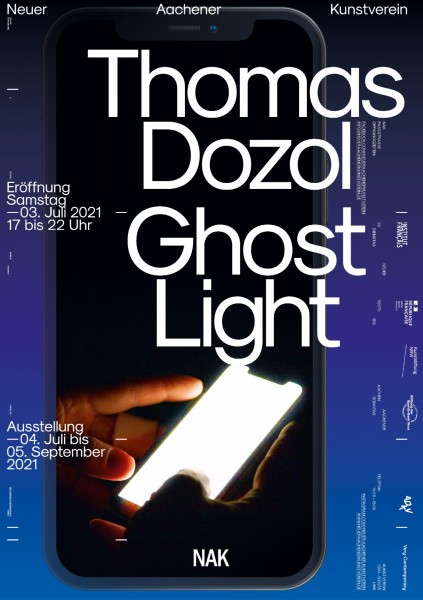

Ghost Light

Thomas Dozol

OPENING:

Saturday 3 July 2021

6 — 11 PM

OPEN:

4 July

—

5 September 2021

Thomas Dozol – Ghost Light

Opening: 3rd of July 2021, 5 – 10 p.m.

Duration: 4th of July – 5th of September 2021

NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein is pleased to present Ghost Light, the first institutional solo exhibition of artist Thomas Dozol.

Ghost Light is an artistic and analytical exploration of the smartphone’s impact on our experience of the world, on what we expect from our connective environment, and on the ways in which we navigate what we agree to reveal – or conceal – about our on- and offline selves.

The constant accessibility and convenience offered by the devices that have come to define our inward- and outward-facing lives in the decade since the release of the first iPhone pose critical questions of loss and gain. As the smartphone has solidified as an extension of the self - as a means of fulfillment in the face of a persistent and emergent threat of sensed emptiness – we must face what it means to operate in the world not only as subjects, but as generators of data and marketable content. Dozol’s artistic strategy confronts this reality with a combination of analogue image printing techniques as well as three-dimensional installation to give an integrated, physical form to the questions posed by dematerialized experience. Through new and site-specific works, Dozol engages in a dialogue of (mis)understanding, using the tension between new technologies and familiar media to navigate the consequences of their interaction.

On view on NAK’s upper floor, the exhibition’s titular installation, Ghost Light, translates data gathered by monitoring the artist’s own phone usage into a temporal light and sound installation. Consisting of free-standing lamps installed in a darkened space, this central work involves an audio component created in collaboration with British musician Matthew Barnes – also known as Forest Swords – who created a soundscape using sounds off Dozol’s phone as raw material which underpins and adds an immersive aural component to the artist’s army of lights filling the room.

Exhibited on the Kunstverein’s lower floor is In Plain Sight, a screenprinted series that seeks to interpret a contemporary phenomena of news consumption. In an age in which a single, portable device delivers a broad spectrum of media - in which the same backlit rectangle is the messenger for both celebrity gossip and hard global news, all skimmed in milliseconds – content is blurred. The import of the information conveyed and consumed are divorced from the materiality of the source. The authority of black and white print is flattened into the same glowing visual mediascape of the tablet, as feeds merge and temporality and urgency are erased into the constant scroll of the indecipherable present. Algorithmically selected content, with its multitude of suggested links, decimates any sense of chronology. Amid these phenomena, In Plain Sight appeals to the clarity and contradiction invited by mobile technology. Each individual work in the series is linked to the release date of a new iteration of the iPhone, timestamped by the superimposition of dated pages of establishment publications such as US Weekly and The New York Times – media outlets that serve as proxies for the interchangeable nature of news and entertainment in the digital age. Overprinting images with covers from both American tabloids and critical journalistic publications, Dozol purposefully questions the equivalences and hypocrisies of 21st century media consumption.

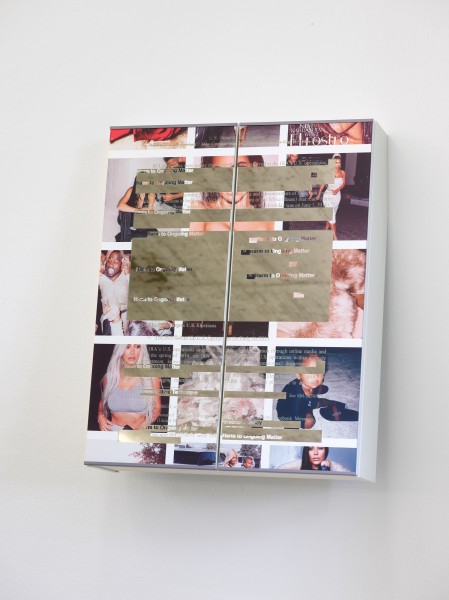

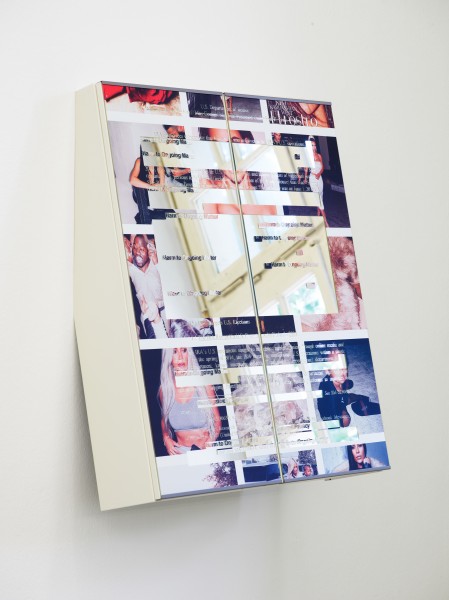

Instagram-era narcissistic behavior – epitomized by the selfie – is explored in a grouping of works on mirrors. Looking back at me to see me looking back at me to see me looking back at me (pretty) and Looking back at me to see me looking back at me to see me looking back at me (masc) is a diptych of mirror cabinets that respond to In Plain Sight‘s look at news consumption as entertainment. Appearing to have sunk into the wall, at different angles one would hold their phone to take selfies before the mirror, most of the surface of the mirrors are obscured by a mix of pages from the Mueller report and screengrabs from Kim Kardashian’s endless Instagram feed at the time the report was being written.

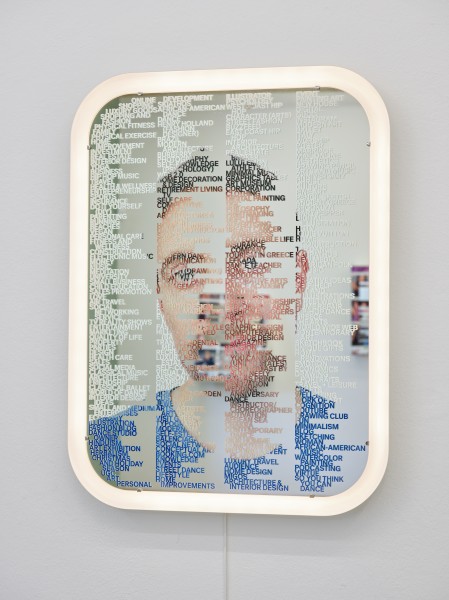

In Self-help, Balenciaga, etc…, keywords assigned to the artist via Instagram’s targeted advertising algorithms form the basis for self-portraiture. The sharpness and immediacy of the mirrored reflection is interrupted by text – “content” that at once is supposed to reveal but in the end obscures and overloads. All these mirrored pieces tempt viewers to take a selfie in the reflective surface of the artworks, then frustrates and ultimately thwarts that very impulse.

Kindly supported by: